Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream

—Edgar Allan Poe

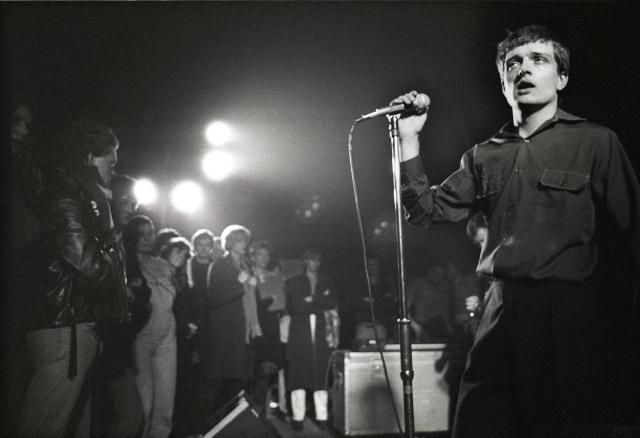

“To the centre of the city in the night waiting for you…” Joy Division’s spatial, circular themes and Martin Hannett’s shiny, waking-dream production gloss are one perfect reflection of Manchester’s dark spaces and empty places. Manchester, as a (if not the) city of the Industrial Revolution, happens to be a more obvious example of

decay and malaise.

Gothic music reiterates that we never get rid of our past, that we are possessed or haunted by our bygones. It underlines psychological detachment. With minor keys, gloomy lyrics and angst-driven singing Gothic music reminds of us of the early Germanic invaders and the threat of the destruction of culture. Something is corrupt and cannot be redeemed. The other aspects of the term Gothic are likewise important: Gothic as a historically marked artistic (especially architectural) movement and as genre of fiction popularized in the romantic era. Both share a gloomy nature that has been reinterpreted in Gothic music since the late 1970s.

Before the term Gothic was popularized by the British press in the early 1980s, the management of Joy Division had labelled their post-punk Gothic. Other bands getting onto the same label around 1979 were Siouxsie & the Banshees and Bauhaus after their debut single “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” (1979), which made a reference to famous Hungarian Dracula film actor of the 1930s. Most of the first Gothic groups were British with some exceptions, such as Christian Death from Los Angeles, Xmal Deutschland from Germany and Birthday Party from Australia.

This article addresses the question of psychological detachment described by bands that can be included under the umbrella term Gothic or dark wave. My aim is to analyse their handling of the themes of alienation and emptiness, which are often related to dream-like states. Answering this question involves both literary and socio-historical analysis. Before turning to lyrical analysis I shall pay attention to the social context of Gothic music; after all, popular music should never be analysed without intertextual and intercontextual references.

I shall use Joy Division and the German 1990s dark wave group Diary of Dreams as my main examples. The repertoires of both bands represent the dark mental spaces and psychological detachment that I intend to analyse. The hollow and haunted spaces described in their lyrics forces the subject (or “I”) into the cage of depressive introspection, hallucination and haunting dreams that is discussed here in terms of trance. While Joy Division sings to “take these dreams away” (“Dead Souls,” 1979), Diary of Dreams deals with “dead end dreams” (“Panik,” 2002a) where the mind is maimed by false identities, lies and corruption. The subject descends into a trance-like state feeling isolated, losing self-control. The only thing left is a feeling of numbness, guilt and a desire to die.

Into the Dark—the Gothic (R)evolution

The post-punk of Joy Division has often been portrayed as a reflection of late 1970s Britain, where industrial modernisation was showing signs of decay. According to Greil Marcus punk culture had seen a rise in the face of mass youth employment, IRA terrorism, growing street violence and racism and the enervation of pop music. The punk sound did not make sense musically, but it did socially. Punk was followed by the more commercial new wave that did not have this kind of social and political meaning. Joy Division’s punk sound was socially squeezed in between paralysed Labour humanism and the immanent cynical victory of Conservatism. Politics had turned into a sombre stage where Ian Curtis’ words echo: “Where will it end? Where will it end?” (“Day of the Lords,” 1979).

Early Joy Division, especially during the Warsaw period in 1977, concentrated on the nihilistic provocations put forward by the pioneer of industrial music, Throbbing Gristle. Like Throbbing Gristle, they played with Nazi imagery and concentration camp numbers (e.g. in “Warsaw,” 1977). Even the name Joy Division is a reference to the Nazi concentration camp brothels where women were held as sex slaves. Punk culture had already popularised the use of the swastika as a countercultural sign and had deconstructed its meaning. In the media, the use of the swastika by punks was read as a link with the resurgent British Nazis. When the racist National Front started to march on the streets of England’s biggest cities, Nazi imagery soon lost its popularity in the punk community. Joy Division chose to provoke through descriptions of inner mental states, dark urban spaces and personal detachment.

Lawrence Grossberg discusses post-punk as a disruption of the category of rock and roll. Post-punk is characterized by desperation, frustration and anger and rejection of the possibility of order and community: “The result is a music that is oddly detached and yet furiously energetic and affective.” In Joy Division punk anarchy has internalized: “This is a crisis I knew had to come / Destroying the balance I’d kept / Doubting, unsettling and turning around / Wondering what will come next” (“Passover,” 1980). Ian Curtis personalized the nihilism of punk: “He sang on the edge, not as a metaphor: his strongest numbers conveyed the feeling that he was fighting against all the odds either to back away from the edge or to go over it.”

It might be an oversimplification to say that Joy Division is a direct outcome of the late 1970s’ political climate, but it is hardly possible to understand their lyrics without taking the social context into account. Joy Division created psycho-social urban maps. The rock journalist Jon Savage even claims that Joy Division helped him to orient in late 1970s Manchester. Joy Division works with isolation and alienation in cities in a state of constant change devoid of social networks. Their lyrics analyse perfectly the personal and social problems people are facing in post-industrial societies. The urban empty spaces in their lyrics function as an analogy of psychological empty spaces.

In Joy Division not only lyrics but also musical sounds underline the emptiness and feeling of psychological detachment. With production mastermind Martin Hannett, Joy Division pioneered the use of new technology such as digital delay that helped them to create a “hollowing” musical soundscape. The echo in Joy Division’s work functions as a metaphor for emptiness. Their lyrics paint a hollow claustrophobic landscape in a state of decay, where the subject is hopelessly doomed and ridden with guilt foreshadowing the suicide of the band’s singer and lyricist Ian Curtis in 1980.

In Germany especially, industrial and punk bands were experimenting with reflections of reality similar to those of Joy Division. Already in 1980s Germany had many relevant groups. Even the former GDR had musical subcultures, including a strong punk scene but also a Gothic and wave scene. Since the 1990s Germany has become the centre of the Gothic world, with prominent artists, a strong fan culture, music media and the largest Gothic festivals. The vigour of the dark scene (schwarze Szene) in Germany shares similarities with the rise of Gothic music in the late 1970s. In the face of mass unemployment, especially in East Germany, and the troubling past with its totalitarian regimes, the escape into dark themes, mysticism and individualism cherished by Gothic culture seems an understandable identity option. Coherent subcultures still have a special place of their own in Germany, while in other contexts there is a lot of discussion regarding the end of subcultures in the face of late modern mediated societies.

Diary of Dreams started their career in the late 1980s as a side-project of singer-songwriter Adrian Hates, who at the time played bass in the similarly minded Garden of Delight. The band released their debut album Cholymelan in 1994. With hollowing electronic soundscapes, Diary of Dreams is a descendant of Joy Division, but also of the 1980s dark wave groups such as Anne Clark, The Cure, Cocteau Twins and Clan of Xymox. Like Joy Division’s, the band’s lyrics concentrate almost entirely on dreamy states involving hate and isolation, depersonalisation, the loss of affection and people growing apart: “I feel like I`m crying / still always denying / and constantly craving / for heavenly places / that I couldn`t find / in your ignorant faces…” (“Monsters and Demons,” 2002).

Both Diary of Dreams and Joy Division depict detaching and alienating spaces that are cultural metaphors of late modern society with distanced and vulnerable social relationships.

Dreams as Labyrinths

One of the precursors of Gothic music had been The Doors, who painted hypnotic mindscapes in songs such as “Riders in the Storm” (from L.A. Woman, 1971). The sinister side was also known from David Bowie (especially Diamond Dogs, 1974) and Velvet Underground. Gothic music portrays hollowing spaces with a fear of something awful coming from below, something echoing from the emptiness. “Is surely recommended not / For fear of death, in fear of rot,” Bauhaus sings in “Hollow Hills” (1990). In “Dead Souls” (1979)

Joy Division describes a troubled past where “mocking voices ring the hall,” in which dreams do not leave the subject in peace, but keep calling him, haunting him. Even more troublingly, in Diary of Dreams not only dreams but reality becomes haunted: “My sanity never in control / Horror-fied, I hate my dreams at night / I wake up without identity / Awaking killing me, I can’t believe I’m breathing” (“Psycho-Logic,” 2004).

Dreadful dream visions have a long literary history spanning from Coleridge to De Quincey and Lord Byron. “The Pains of Sleep” (1803) by Coleridge described dreams as “[…] the fiendish crowd / Of shapes and thoughts that tortur’d me […] For all was Horror, Guilt, and Woe, […] Life-stifling Fear, soul stifling Shame!” In Confessions of an English Opium-Eater De Quincey depicts a similar vision: “I seemed every night to descend, not metaphorically, but literally to descend, into chasms and sunless abysses, depths below depths, from which it seemed hopeless that I could ever re-ascend. Nor did I, by waking, feel that I had re-ascended.” Like “Psycho-Logic,” the dreams described in Quincey’s opium labyrinths seem to continue even when waking. Dreams and reality become blurred.

Charles Nodier describes the fusion of dreams and reality in his essay on prison etchings by Piranesi. His Carceri etchings (ca. 1749–1750, 1761, in English prisons) had an impact in England on writers such as Horace Walpole, William Beckford and De Quincey. In France, the Carceri influenced authors like Hugo and Baudelaire. Nodier’s essay describes how Piranesi is endlessly trapped in his own labyrinth; without end, he is finding new stairs and new doors, a theme that is portrayed on some Gothic record sleeves such as Aus der Tiefe (2005) by the German Gothic group ASP. Nodier’s descriptions of what he calls “reflexive monomania,” a phenomenon in which fact and fiction are blurred, anticipate later psychoanalytical notions of dreams. Psychoanalysis is itself quite a Gothic invention: subjects cannot even be sure of their own identities, making them strangers to themselves. “Something must break now / This life isn’t mine” sings Ian Curtis (“Something Must Break,” 1980). Diary of Dreams illustrates a collapse of self: “Perverted dreams my fractual binding / as my puzzle falls apart / logic questions existence / of this strange phenomena […] / believe me saying, it’s not the skin / It’s the stranger inside” (“Predictions,” 1999).

Strangeness and alienation relate strongly to nineteenth-century literature. The metropolis had become a modern equivalent for a Gothic castle—Gothic literature became urban. Poe had written on the uneasiness of the crowds in his “Man of the crowd.” E.T.A. Hoffmann portrayed his silent watcher of Berlin. Big cities started increasingly to produce uncanny feelings during the nineteenth century. In Joy Division, the city has turned into a Piranesian labyrinth: “Down the dark streets, the houses looked the same / Getting darker now, faces look the same / […] Trying to find a clue, trying to find a way to get out” (“Interzone,” 1979). Freud writes in his essay on the uncanny of a similar experience of getting lost in an Italian city and always returning into same spot, the experience he describes as unnerving and dreadful. Freud’s experience echoes the writings of late nineteenth-century sociologists writing on alienation (Marx), strangers (Simmel) and anomy (Durkheim).

In Joy Division the feeling of being isolated is enforced by visions of decay and disorder hinting at the works of J.G. Ballard: “It’s getting faster, moving faster now, it’s getting out of hand / On the tenth floor, down back stairs, it’s a no man’s land / Lights are flashing, cars are crashing, getting frequent now / I’ve got the spirit, lose the feeling, let it out somehow” (“Disorder,” 1979). As a proto-cyberpunk work, Ballard’s Crash (1973) is the cult book of industrial culture that was also read by Curtis. Crash describes estranging cityscapes where people feel so detached and numb that they start to purposely cause car accidents in order to feel something. The mumbing effect of mediated and riskconscious society leads to a feeling of depersonalisation that is only overcome by destruction. Ballard’s book is an excellent example of how the feeling of the Gothic uncanny pervades late modern societies: the fantasies of dead celebrities, the media presence of accidents and estrangement of the subjects to the extent that death becomes a medium of life—“Time for one last ride / before the end of it all” (“Exercise One,” 1978).

While Joy Division describes late modern cityscapes with crashing cars and flashing lights, Diary of Dreams refers to the medical aspects and psychotechnical aspects of modern life such as “soul surgery, electric dream treatment” in Pain Killer (2002). Soul Stripper (2002) and Verdict (2002) mention the overdose and “Eyesolation” (1996) of the needle: “But who have I to blame? Just the cripple of my fear just call my disguise / the needle serves me well.” Isolated dream-states refer to drugs as a saviour: “I need my chemicals / Are my dreams gone? / Are my words forgiven? / Are my deeds undone? / Am I now forgiven?” (“Chemicals,” 2000). On the sleeves of Freak Perfume (2002) Adrian Hates is portrayed dead on a pathologist’s slab. The concentration on drugs, self-harm and hate is not so strong as, for example, in the lyrics of industrial rockers Nine Inch Nails,31 but Diary of Dreams still clearly asserts that life in itself may be merely a perverted dream and endless trance-like labyrinth. In this decadence, the Eden of self has become a hell of selfconsumption.

Alienation of the Self

Search for a flower in ice

Do not tranceform into a slave of lies

—Diary of Dreams, “Never!Land” (1998)

The hollowness depicted in Gothic music is all about personal distance. Its lyrics describe dying emotions, numbness and getting lost in a reality that is not one’s own. They represent a spatial transformation or rather trance-formation of the psyche distanced from the others. In the lyrics of Joy Division and Diary of Dreams the self is often chained or paralyzed, but still distant from anyone else, and life is plunged into isolation and coldness: “I’m living in the Ice Age / nothing will hold / nothing will fit / into the cold / no smile on your face” (Joy Division, “Ice Age,” 1977). The loved one in the lyrics is fading away or the love is tearing the lovers apart. In Diary of Dreams’ “Never!Land” the creative scope of life turns into lies and distance underlined by distance and trance formation. The song ends in personal paranoia: “And now you know I’m doubting / everything you offer me in this demented world.”

The trance state is referred to in several of songs by Diary of Dreams and in “Walked in Line” (1978) by Joy Division. Trance states have often been addressed in anthropological studies. They are usually related to magicoreligious practices that manipulate organisms, for example, by the use of hallucinogens, sleep deprivation and extensive dancing. Here I am particularly interested in trance as a state related to social isolation with sleep and dream states characterised by the possession of the other. Gregory Bateson describes trance as an ego-alien state where the subject’s vision of his own self and body is distorted: “I can see my leg move but ‘I’ did not move it.” Joy Division perfectly outlines the trance in “She’s lost control” (1979):

Confusion in her eyes said it all, she’s lost control

And she’s clinging to the nearest passer by, she’s lost control

And she gave away the secrets of her past and said “I’ve lost control again”

And of a voice that told her when and where to act, she said “I’ve lost control again”

[…]

And she screamed out kicking on her side and said “I’ve lost control”

And seized up on the floor, I thought she’d die, she said “I’ve lost control”

The trance is emphasized in “She’s Lost Control” on both the musical and the lyrical level. The constant use of repetition is part of the dream-states that Joy Division creates. Some of their lyrics are even virtually impossible to grasp without hearing the music. In popular music, songs are not only text or poetry, because the music and musical performance gives meaning and context to the lyrics. In “She’s Lost Control” singing and drums have a strong throbbing echo. In the lyrics the loss of self-control is systematically repeated until the end of the song. This is even more underlined in the extended version of the song (1980): the narrator starts to doubt his own life and loses control of himself too.

Trance was also part of Joy Division’s live performances. The shows were well known through the manic stage presence of Ian Curtis with his “dead fly dance.” Curtis had been diagnosed as epileptic and his wife saw this dance as a “distressing parody of his offstage seizures;” toward the end of his life he even possibly suffered them on stage. It is worth mentioning that trance-states share a similar pattern with epilepsy. Although Ian Curtis’ dance moments may have been structured and precise, his dancing left a substantial influence on Gothic music and culture: it presents music literally on the edge of losing one’s mind.

Losing one’s sanity is devastatingly portrayed in Joy Division: “Now that I’ve realised how it’s all gone wrong / gotta find some therapy, this treatment takes too long / deep in the heart of where sympathy held sway / gotta find my destiny, before it get too late” (“Twenty-four Hours,” 1980). In Diary of Dreams the self is portrayed as shattered: “Apocalyptically divided / mentally disturbed they call me” (“A Sinner’s Instincts,” 1997). Both bands portray subjects being out of control in schizophrenic situations. “Amok” (2002) by Diary of Dreams puts this double-bind of self clearly: “I am-ok, if am-ok, you see…. / Don’t be such a stranger / I am-ok, but you’re in danger! / You say my dreams have all turned grey / How ignorant of you to say! / You claim that you can feel my pain / Insane of you to stay!” Note the word play on “am ok”/“amok”—sanity becomes fused with insanity.

The end of the nineteenth century was full of mirror images of falling into decadence: Dr. Jekyll encountering Mr. Hyde in the looking-glass, Dracula looking into the empty mirror and Dorian Grey staring at the metamorphosis of his portrait. The romantic doppelganger had changed and multiplied the self, and the distinctive boundaries between interiority and exteriority, self and other and past and present had collapsed. “Amok” presents this kind of distorted self-image where subject is at the same time ok and not ok. One’s own ambivalence is mirrored through the other: “I put so much faith into you / I trusted everybody except myself.” In Diary of Dreams and Joy Division the subject is facing constantly huge problems with his own identity. He is lost. The “I” does not know who he is and how he should act. Joy Division exemplifies this perfectly: their lyrics are full of guilt-ridden anxieties involving the question of how to choose.

The subject in Joy Division and Diary of Dreams is trapped in a state of melancholy where past becomes blurred with present: “The past is now part of my future / The present is well out of hand” (Joy Division, “Heart and Soul,” 1980.) Something is lost and cannot be regained and only thing left is wounds: “The scars just cannot heal” (Diary of Dreams, “Oblivion,” 1996). Consequently, the subject is stuck in past traumas: “Portrayal of trauma and degeneration / The sorrows we suffered and never were free” (Joy Division, “Decades,” 1980). The loss of object is followed by the in-between position that belongs neither to subject nor to object. Julia Kristeva calls this abject. Abject is something that has no identity or order; it is constantly in between, breaking the boundaries between inside and outside.

According to Kristeva, shame, guilt and seeing oneself as dirty relate to the abject. Shame in Joy Division is often depicted straightforwardly: “I’m ashamed of things I’ve put through / I’m ashamed of the person I am” (“Isolation,” 1980). Similar tones of self-hate can be read in the lyrics of Diary of Dreams as well from the lyrics of other dark wave bands: “I will never be clean again” (The Cure, “The Figurehead,” 1982). A world that is corrupt and saturated with lies seems to be one of the favourite themes of Gothic music. Corruption, breaking the order, lying and abuse are all abject phenomena: “Feel, fake—reject my touch / shiver, shake—don’t trust my language” (Diary of Dreams, “E.-dead-Motion,” 1998).

The lyrics of Diary of Dreams are full of accusations, self-hate and hate of the other: “This is my gift for you / this is my therapy of hate / this is the poison room / this is your home my friend” (“Reign of Chaos,” 2004). In Diary of Dreams the woman often turns into a femme fatale, a popular theme in the art and literature of the end of the nineteenth century that can be read related to masculine fear created by the new place of women in society. The woman is represented as a corruption draining men’s life force, as in Charles Baudelaire’s poem “Les métamorphoses du vampire” where a man searches for love but finds only death. Yet, in the lyrics of Diary of Dreams the subject sometimes blames himself for all the mistakes he has made. Self-hate and hate of the other become fused—perverted. The abject experience is hence returning to primary narcissism where there is no border between self and other. All that is left is a devastating experience of loss and emptiness. The dread of abjection follows the dissolution of borders and homelessness. The question “who am I” has turned into a desperate cry: “where am I?”

Gothic Modernity

The broken hearts, all the wheels that have turned

the memories scarred and the vision is blurred.

—Joy Division, “From safety to where…?” (1979)

I know one thing for sure, I have doubts about life, but none about death

I have hopes about death, but none about life

—Diary of Dreams, “Dead Letter” (2004)

The end of the twentieth century has been interpreted as a revival and reenactment of some themes that were dominant in fin de siècle literature. Technological societies arising since the end of the 1970s raised the question of identity in perhaps a more crucial way than ever before. Who am I really, if even the material surroundings of society and institutions are in the constant state of becoming, in a flux? The subject-object relations of society and culture have become increasingly blurred. Our techno-commercial societies offer luxurious freedoms for identity construction and lifestyle changes, but paradoxically there is simultaneously a constant identity crisis and the quest for the authentic true-me. Our late modern way of life maximises freedoms but also loneliness. “Many are afraid that supportive social bonds will evolve into bondage,” as David A. Karp underlines in his work on depression.

The revival of the Gothic in late modern culture arises from the uncertainty of self in a changing society. The Gothic music and lyrics analysed here are perfect examples of late modern wound-culture—a culture that is constantly occupied with personal trauma and misery as spectacle. Wounds (or trauma) are constantly repeated without hope of healing. Subjects are filled with uncertainties and at the same time there is a gulf of loss hollowing the mind. Something is lost but cannot be retrieved. World and self have no place, they are perpetually deceived and left to decay. The subject feels isolated and alienated and is left with a trance-like dream reality.

The works of Joy Division and Diary of Dreams underline personal emptiness, ambivalence and dream states. Their lyrics describe the logical road from social milieu to social isolation. Alienation and failure in relationships lead further into loss of self control. The strongest enemy is one’s own self—the Gothic enemy within. This depressive state is like a cancer. Death feels like an ultimate chance to escape a dead-end situation caused by a reality that is not one’s own. This desire for death in Gothic music involves both nostalgia and perversion. The longing for death can be interpreted as a wish to return to the original state before the loss of object. However, the very same wish perverts life, merging the boundaries between life and death, life becoming a life in death.

Gothic music uses the abject imagination—it works with the uncanny aspects of life, but there is a dark hope involved in the assumption that anything, even pain, is better than not feeling anything at all.49 The “death disco” of Joy Division and other Gothic groups involves a positive frame in the face of eminent darkness. The power of the music comes from the contrast between darkness to light, from dark lyrics to pop melodies.50 Turning angst into culture does not mean the production and repetition of that angst, but rather its cultivation—the sublimation of darkness.

© Atte Oksanen