Every year, millions of fans shuffle up the Boulevard de Belleville in Paris and chart a course through the crumbling headstones and gothic mausoleums of the Pere Lachaise cemetery to pay homage at (and maybe pour a fifth of bourbon on to) the grave of Jim Morrison. Similarly, in New York, 72nd street and Central Park West is probably one of the city’s most loitered-on corners, jammed with tourists who stand in solemn contemplation at the spot outside the Dakota building where John Lennon was gunned down by Mark Chapman. And in Memphis, Tennessee, the Presley estate continues to turn a dime well over 30 years after Elvis’ death by traipsing busload after busload of Japanese tourists through the gates of Graceland.

On the face of it, there’s not a lot to differentiate Ian Curtis from any of those other dead rock stars, right down to the humble headstone in Macclesfield cemetery that attracts its own steady stream of disciples. The Joy Division frontman may not be a fully paid-up member of what Kurt Cobain’s mother once called “that stupid club”, his application having been expedited by his own hand at the age of just 23 rather than 27 – but he certainly deserves a certificate or something. Like many members of the club, he found far more success in death than he ever did in life – though admittedly he never gave himself much of a chance – and like all of them, he was a complex, tortured soul, who made some suspect choices, upon whose head deification does not rest easily.

All those aforementioned names are keenly missed of course, but thirty five years after his death, Ian Curtis remains possibly the most tragic figure of them all, a monumental waste of a once-in-a-generation talent.

Even by the standards of potted rock biographies, Curtis’ makes for depressingly brief reading. Born in Stretford in July 1956, he was a bookish youth who showed an aptitude for poetry, but ended up married at the age of just 19, with a job in the civil service. In 1976, he met Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner at a Sex Pistols gig and formed Joy Division. Two years later, the band signed to Tony Wilson’s Factory Records; a year after that, they released their seminal debut album ‘Unknown Pleasures’. After being diagnosed with epilepsy that same year, Curtis’ condition worsened with the pressures and anxieties of touring, and in April 1980, he attempted to kill himself with an overdose of barbiturates. The next month, on the eve of Joy Division’s first American tour and six weeks before the release of the band’s second album, ‘Closer’, he succeeded by hanging himself in his kitchen.

There’s an obvious answer as to why, three and a half decades later, Ian Curtis is still so mourned by so many. It’s because, unlike Lennon, Morrison, Hendrix, Jones or even Cobain, his flame was snuffed out before he’d really started. Joy Division’s final album and their first EP were separated by a gap of less than two years; that’s two years in which they managed to define British post-punk and change Manchester music forever. Had he lived even just a little bit longer, who knows what he may have gone on to accomplish. In any case, it seems a safe bet that we’d be writing these words in a very different musical climate.

But what-ifs aren’t enough to sustain the kind of legacy that Curtis has left behind. What endures about him isn’t some misplaced romantic notion of dying young enough to have never made a shit album, either. His suicide arguably amounts to nothing more than a default on an unlimited promise and – far more seriously – giving up on his young wife and child. Only ghouls and morons will find glory in that act; for the rest of us, it was merely the most selfish decision he ever made.

As far as ‘Realness’ – that most misunderstood of rock commodities – goes, Curtis meant it, alright. The pain and alienation he sang about, his explicit disgust and confusion with the world that drips from the lyrics of ‘Atrocity Exhibition’ and ‘Disorder’ like blood down a grey granite wall, is as authentic as rock and roll gets.

Lyrically, he held nothing back; his themes were wrapped in elegant, poetic phrasings, but even the most casual listener can discern the deep unhappiness and loneliness within them. Curtis placed no emotional distance between himself and the listener; listen to the lyrics of ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ and he paints you a picture of something as intimate and painful as the collapse of his own marriage, blowing the fourth wall to smithereens. The blunt honesty and brutal frankness of that song still sounds shocking no matter how many times you hear it – Curtis doesn’t even try to deflect blame; the only side he takes is against himself.

Yet few artists do open themselves up so willingly on record, and it’s a sad fact that many of those people – like Kurt, Richey or Elliot Smith – end up taking their own lives, after making ours that bit richer. But instead of making a martyr out of Curtis and celebrating him as some sort of self-sacrificial lamb, it’s his honesty and fearlessness that he should be lauded for, not his devastating denouement.

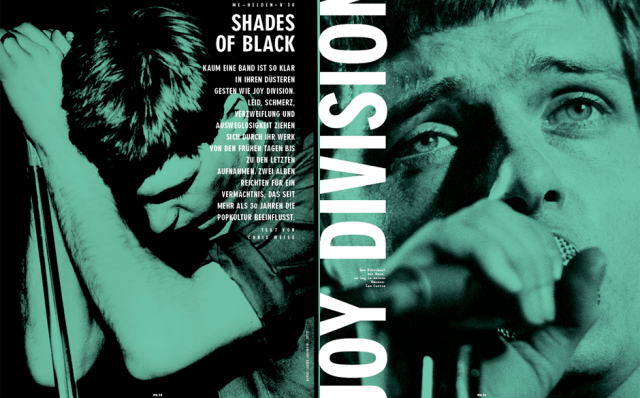

Nevertheless, Ian Curtis continues to fascinate us because we inevitably want to know more about him than we’ll ever be able to. His is a well-preserved but enigmatic ghost; his pale, haunted eyes stare out at us from a finite number of starkly beautiful black-and-white Anton Corbijn shots, a handful of television appearances, one music video, and very little else. He never lived long enough to be overexposed.

Or to explain himself. Curtis was a man of deep, deep contradictions; a sensitive artist with a taste for bohemian writers like Burghs and Ballard, he was also a loyal Tory voter, who vehemently opposed immigration and flirted with fascistic imagery. In her 1995 biography Touching From A Distance, Deborah Curtis characterized her husband as a man who veered between good-natured generosity and selfish control-freakery, and who she once suspected of having homosexual affairs.

He was certainly adept at living a double life, and not just from Deborah, who he was unfaithful to for long periods of time with Belgian journalist Annik Honore. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see Ian’s inner turmoil exert itself through his lyrics and manic performances, but away from the stage, his welling melancholy was well-hidden from the bandmates he didn’t want to alarm or disappoint. Even as he was planning to kill himself, he convincingly feigned enthusiasm for Joy Division’s upcoming American tour, so much so that drummer Stephen Morris has admitted that, “Looking back, I wish I’d helped him more. I think that all the time… But we were having such a good time, and you’re very selfish when you’re young. Epilepsy wasn’t understood then. People would just say, ‘He’s a bit of a loony – he has fits.’”

Peter Hook, meanwhile, was more characteristically blunt.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “He must have been a pretty good actor. We didn’t have a bleedin’ clue what was going on.”

Only Curtis himself can offer clarification of what went on in his head and well… Because when it comes to the past, the truth is often subjective, dictated by those with axes to grind or agendas to protect. We’ll never really know who Ian Curtis was. But that, of course, won’t stop us from wondering.

Even Anton Corbjin’s acclaimed 2007 biopic Control raised more questions than it did answers. The film was praised in many quarters for portraying Curtis in a distinctly human light and not as a tragedy waiting to happen. But for his daughter Natalie, the film didn’t go far enough. “Control’ doesn’t go far enough to convey my father’s mental health problems,” she says. “His depression and mood swings are simply not addressed. Given the fervor to discover why he killed himself, this is something of an oversight.”

Yet, for all the unanswered questions, for all the failings he may or may not have been guilty of, Ian’s legacy is one of rock n’ roll’s most fiercely guarded and respected, and rightly so. You certainly won’t see an Ian Curtis avatar spasming awkwardly around a pixilated stage to the strains of ‘Livin’ On A Prayer’ in the next edition of Guitar Hero. Even something as well intentioned as Peter Hook’s decision to mark the 30th anniversary of his friend’s death by playing ‘Unknown Pleasures’ in its entirety with his new band at FAC251 in Manchester was met with tuts of disapproval – though having been there and lost something in the process, who are we do judge how Hooky choose to celebrate his friends life?

Ultimately however, we should be bothered about how Ian is remembered. If we didn’t the absolute worst-case scenario would be a wave of tasteless, commercialized nostalgia that cheapened his achievements.

Musically, Joy Division aren’t quite as in vogue as they were a few years back, when the likes of Interpol, Editors and Bloc Party mined their brand of kinetic new-wave guitars and baritone melancholy for ideas; paradoxically, it’s New Order who are the big thing right now. But such is Joy Division’s importance, they never stay out of fashion for very long. And with the gloom that’s currently enveloping this country (if you believe the daily papers at least), it surely won’t be long before another generation of pale, undernourished and disenfranchised youths in three quarter-length overcoats prick up their ears to the cataclysmic rumble of ‘Transmission’ or ‘She’s Lost Control’. They may well already have done so.

It seems ironic that it’s the date of Ian Curtis’ death – May 18th – that has been chosen to celebrate his life. As Peter Hook once said of his suicide, “It was a permanent solution to a temporary problem,” and an unfortunate decision that brought him the worst kind of immortality. You can speculate endlessly on how different things might have been had he lived, what kind of person he really was, or what his final thoughts were in his still-unpublished suicide note. But in the end, the man himself remains rock n’ roll’s greatest unknown pleasure. The music is all that’s left of him, and what a body of work he left behind.

This piece originally appeared in NME, May 22 2010