Introduction

To date, no mainstream pop act has emerged from the ‘disability arts’ scene, a phenomenon most observers place as starting in the 1980s. Likewise, few professional musicians with innate or acquired mental or physical disabilities have direct experience of the disability rights movement, with the well-known exception of British singer Ian Dury. However, attitudes towards public display of both mental and physical impairment can be seen to alter in tandem with political changes that began with the nascent disability rights movement in the 1970s and came to more general consciousness from the 1990s forward.

This is good news for musicians – or is it? From another point of view, one can argue that as part of a music-marketing discourse that thrives on new and better ways to construct ‘otherness’, disability can be deployed as just one more attribute that sells records. Rather than heralding acceptance of disability as part of the typical human condition, evidence can be mustered indicating that in pop it still tends to be used as a device for constructing musicians as exotic outsiders, a saleable commodity in an industry that sees ‘authenticity’ as currency. There is a danger that this marketing discourse can stray into the territory of what David Hevey (1992) has called ‘enfreakment’: the use of the attraction/repulsion of difference to sell tickets or products whilst marginalising the performers themselves.

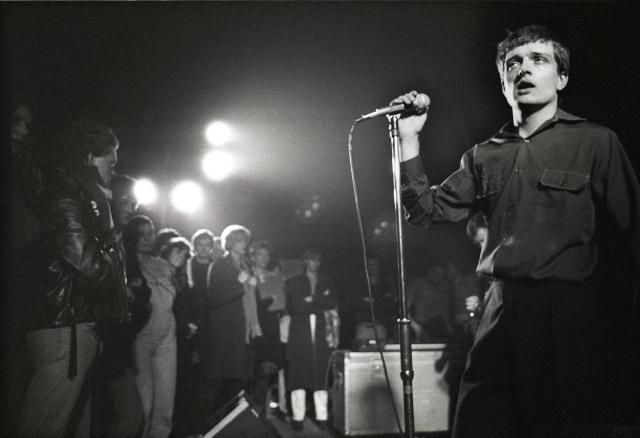

For the purpose of this research, we have chosen to examine marketing materials that illustrate the evolution of ideas about disability in music, both relating to lead singer Ian Curtis of Joy Division. The first set are those made available during the band’s brief heyday in the late 1970s, the other emerged to market reissues and films related to the group considerably later. As we will show, the differences between these materials are striking less for exhibiting changing levels of appreciation for diversity than for the move back towards a more tabloidesque use of disability to create and maintain romantic images that sell products.

Marketing Joy Division, the first time around

Of all the terms in the terrains of popular music discourse, the notion of authenticity is perhaps the most fiercely contested. With it is inscribed the sense of the real, the honest and truthful spark that lies at the heart of genuine performance. Of course, each of these notions is inherently bound up with the ideals of authenticity, and they are fought for in the process of authentication.

It has been argued (Rubidge 1996; Moore 2002) that authenticity is not inscribed in either art or artist, but is something ascribed in the process of interpreting the performance. But it is in the actual attribution of authenticity as confirmation of creative merit that we can view the impact of the mediation of art, artist, genre and the historical perspective surrounding the event.

Authenticity is attributed in the music industries through the wider discourse of Romanticism, which presents an understanding of the artist as an autonomous, creative individual who exists outside of any commercial realm. Marshall notes that this position allows a space whereby the fan comes ‘to see the record industry as unable to reflect the whole creative range of their artist and, furthermore, position

the industry as against their artist’ (Marshall 2005, p. 156). It is in the contours of this Romantic notion of outsiderness that concepts of artist as tortured soul are encouraged. The dialectic of Romanticism ascribes meanings, which appear uncensored, unauthorised and authentic. And yet it is through the very mechanisms of the music industries that the fan is able to read these meanings.

The mediation of popular music events in the music press has fully exploited this relationship between artist as outsider and art as commerce. Journalists snatch brief moments in a historical flow, isolating and magnifying them in the process. These snapshot events become mythologised as being the authentic urge evidenced. Witness the romanticisation of the artist on a path of self-destruction, a narrative in which individuals like English singer Pete Doherty are captured in moments of personal darkness but represented as iconic examples of the rock and roll dream personified.

At present, drug addicts, alcoholics and self-harmers are all represented as somehow more authentic than others in the pages of the music press. Authenticity, then, is hard won for the individual. And yet it is an ideal, which shifts in its meanings as much as the signposts that point towards the ideal are fluid in form. The MDMA casualty of the late 1980s Balearic scene is invested with a notion of honesty, while without artistic output to justify self-abuse, the young suburban raver damaged by an excess of ecstacy pills does not rate so highly. The highly publicised drug-related arrest of musician AmyWinehouse and the sectioning of singer Britney Spears have revealed that the badge of authenticity is also genre specific.Winehouse is represented as a serious musician who taps into the depths of the soul music greats. Her drug use is by inference entrenched in the very nature of the music; her greatness is that she feels in the same way that Ray Charles felt. Spears, on the other hand, is represented as a trashy mother whose mental health issues have made her an out-of-control laughing stock. In the narrative of authenticity, Spears has no need to ‘feel’ as her ‘art’ is disposable pop, and as such the embodiment of music as commerce.

Joy Division existed in a post-punk arena that fully embraced the ideologies of Romanticism. Musically they exploited brooding, minor keys with a punk sensibility. ‘Suffice to say Joy Division do have a Sound/Style that is their own’, wrote drummer Stephen Morris on the press release for their debut An Ideal for Living EP (1978). Lyrically Ian Curtis indulged in the classic explorations of the outsider, drawing on the emotionally charged rhetoric of the individual who feels more than others do, the young man with heart and soul. The band’s imagery also explored this ideal of detachment from the brutal, unfeeling world. Cover art often represented the distant observer. Transmission (1979) offered the stargazer’s night sky, Unknown Pleasures (1979) a print-out of the flashes created by a dying star. ‘Atmosphere’ (1980) was illustrated by the snow-coated desolate landscape, where life only happens in the distance. Closer (1980) offers the voyeur’s view of Romantic emotion immortalised in lifelike statues of the Staglieno Cemetery in Italy.

If, as the surviving members of the band would later claim, the public image of Joy Division was miles from the truth, then it could be argued that they were in the process of contesting their own right to the claim of authenticity – a PR exercise common to all bands that emerge from rehearsal rooms to perform in live venues.

The music press quickly embraced Joy Division as serious artists whose very presence was bathed in an intellectual glow that the post-punk era now demanded. This image was strengthened by journalist Paul Morley’s often-oblique features on the band (2008), in which they were portrayed as timeless and ethereal, an image captured not least in Anton Corbijn’s critically acclaimed black and white photo of the band walking through a tube station, with only Curtis looking back – the individual out of sequence with the moment.

In later years Curtis would come to embrace this public image rather than the laddish behaviour usually indulged in by the band. According to bassist Peter Hook in the sleeve notes (also supplied as press materials) to the 2007 reissue of Closer, Curtis developed the serious persona to impress his then-girlfriend from the continent, Annik Honoré: ‘Ian did start to bring Annik, and that changed the whole dynamic of everything’, he says. ‘He wanted to impress Annik as being this arty, tortured soul, reading poetry, plumbing depths . . . He was the sensitive artist in front of Annik, and we were buffoons’ (Hook, in Morley 2008, p. 124).

The Romantic ideologies used in representations of Joy Division were all drawn from meanings that were attached to the commodifying process. Part of this process was the way the band was sold to the music press. Ironically, the promotion of any single band or artist actually flew in the face of their record label’s ideology. Factory, an imprint whose owner Tony Wilson revelled in the concept of the whole being greater than the individual, was about the concept in its entirety; individual artists were merely a part of the concept (hence the habit of providing everything from posters to records, clubs to personnel with a FAC serial number).

The early meaning of Joy Division, then, was attributed through Factory Records’ artefacts, all of which were closely controlled by the label’s in-house designer Peter Saville. Indeed, the UK press release mailed with the original edition of Closer was suitably short on information about band or singer, it merely heralded the band’s second album. Stark minimalism was the Factory style du jour. Despite the label’s eclectic roster of artists, such as A Certain Ratio, the Durutti Column and Happy Mondays, Factory’s ideology was one that did not promote individual difference. This original marketing still exerts power – so good it was not noticed. For example, in an interview with the Chicago Tribune, Nine Inch Nails frontman Trent Reznor says:

For the last five years, Joy Division has been one of my favourite things to listen to. There was something pure about them; it doesn’t feel like marketing was involved in that sound, or manufactured hype. It was just a pure, simple, brutal, ugly thing. There is a purity to it. Today’s bands have recycled it. There is a shiny new, NME-approved pet band every week. But it doesn’t feel as sincere or as long lasting or as important as Joy Division’s music still does. (quoted in Kot 2008)

In keeping with the Factory philosophy, with the onset of Ian Curtis’s epilepsy in 1978, the label initially attempted to suppress information regarding this ‘difference’. Photographer and Joy Division associate Kevin Cummins categorically states that the label never used Curtis’s illness in the promotion of their records, either at the time or posthumously (Cummins, personal communication, 2008). It is also true that epilepsy was never mentioned in any of the band’s live reviews at the time. Skids front man Richard Jobson (Nice 2006) states that the members of the band never even discussed Curtis’s seizure disorder with their lead singer – Curtis had, however, spoken about it with Jobson, who also had epilepsy.

Curtis had quietly addressed the experience of epilepsy in the lyrics of ‘She’s Lost Control’ (1978) recounting how he thought a former client of his may have felt when having a seizure (Gee 2007). At the time, he was juggling work as a musician with a full-time day job as an employment officer for people with disabilities. However, the lyrics were sufficiently oblique and personal that casual listeners would not necessarily have picked up on it, nor was the song’s topic highlighted by contemporary reviewers. In a 1980 letter, though, Curtis articulated his own experience in terms of his memories of working with people with disabilities.

I feel it more as I used to work with people who had epilepsy (among others) and every month used to visit the David Lewis Centre as part of my job. All the very bad cases are there for treatment or just to be looked after. It left terrible pictures in my mind. (quoted in Church 2006)

According to David Church, ‘Though he speaks indirectly in the song as the woman, an additional verse was added in late 1979, perhaps as a way to personalize a song originally written about someone else’s disability experience’ (Church 2006).

When Curtis was helped off stage following an epileptic fit by an ambulance crew in March 1980, Bristol fans (like those who witnessed similar scenes at other venues) were none the wiser. For all they knew, it could have been a modern echo of James Brown’s well-worn concert finale schtick. And when Crispy Ambulance vocalist Alan Hempsall stepped in for a ‘too ill’ Curtis for a concert in the following month, audience members were angry but in fact still ignorant to the medical truth behind the situation.

If the suggestion has been that Factory and the band were being sensitive to the situation by not broadcasting the truth, then moves to replace Curtis would suggest otherwise. And although surviving band members and Factory personnel deny it, the use of a tombstone (again from the Stegliano Cemetery) for the cover of the post-suicide single ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, suggests the tragedy of Curtis had become a commercial artefact, subsumed by the label’s ideology.

The construction of Romantic authenticity: the remarketing of Joy Division

It is only in later marketing materials that we see disability – Ian Curtis’s seizure disorder and depression – used in an obvious way. For the music media, his suicide on 18 May 1980 became an authenticating act for which a meaning became inscribed through analysis of lyrics. Press materials for subsequent collections Substance (1988) and Heart and Soul (1997) represent Curtis as a tragic figure, alluding to the secrets that can be discovered in his words. However, the impact of epilepsy on his mental well-being, and perhaps on the particular form and content of his art, continued to be left out of the story.

This can be seen as merely an echo of a Romantic narrative that is at least as old as Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774): indeed, one version of the Curtis narrative is that his final depression and suicide were the result of being embroiled in a Werther-like fatal love triangle, a version that also avoids the impact of his seizures, the medication he was taking for them, and the social stigma

attached to the condition from the tale – though it is a conclusion listeners might take from the lyrics of Joy Division’s hit single, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’. Events surrounding Werther are frequently noted as a key early example of a youth culture phenomenon spawned by a mass-media product, with passionate readers adopting the lead character’s eccentric dress style and, allegedly (though this has never been conclusively documented), committing suicide in droves (Phillips 1974).

Disability in the form of illness, markedly tuberculosis, was closely associated with the aesthetics of Romanticism – Goethe himself was said to be a sufferer. In the late eighteenth century, Jean and Réne Dubos write:

Tuberculosis . . . may have contributed to the atmosphere of gloom that made possible the success of the ‘graveyard school’ of poetry and the development of the romantic mood. Melancholy meditations over the death of a youth or a maiden, tombs, abandoned ruins, and weeping willows became popular themes over much of Europe around 1750, as if some new circumstance had made more obvious the ephemeral character of human life. (Dubos and Dubos 1987, pp. 44–5)

That new circumstance was the spread of tuberculosis. Part of the appeal, of course, was that the disease produced a characteristic appearance that came to be seen as itself romantic – the forerunner of the ‘gothic’ look, as it were. As Henri Murger has his pianist character Schaunard joke ruefully in Scénes de la Vie de Bohéme, ‘I would be as famous as the sun if I had a black suit, wore long hair, and if one of my lungs were diseased’ (ibid., p. 50).

This is a very different use of disability as a marketing tool than the one most typically retailed in the modern era. Lerner and Straus note that impaired musicians are more frequently captured within the ‘overcoming narrative’, as plucky fighters who have fought disability to make art (Lerner and Straus 2006, p. 2). These stories have long been sales-pitch fodder for promoters, such as those who paraded the Black, blind and possibly autistic pianist billed as ‘Blind Tom’ on the nineteenthcentury concert trail (Southall 2002).

This common trope can run in tandem with the myth of the ‘mad genius’, the person whose difference supposedly allows him or her to stand apart from typical individuals and create unique art. In recent years there has been a re-examination of this narrative, as exemplified by Kay Redfield Jamison’s research (1996), questioning whether there may be a quite real linkage between ‘madness’ and creative genius. Along with Jamison, neurologist Oliver Sacks has made a strong argument for accepting that some conditions seen as impairments by society may also bring with them a gift. He writes:

Creativity is usually in a different realm from disease. But with a disorder like Tourette’s syndrome, especially in its phantasmagoric form, one may have the rather rare situation of a biological condition becoming creative or becoming an integral part of the identity and creativity of an individual. (Sacks 1992, pp. 15–16)

The idea that certain neural networks are specialised for processing music has been further explored by neuroscientists (for example, Zatorre 2001; Peretz 2001; and Sacks 2007), often with reference to musicians who have neurological impairments. A particular role has been posited for a linkage between temporal lobe epilepsy and artistic achievement (Waxman 2001), and particularly between temporal lobe epilepsy and hypergraphia – the drive to produce creative writing or painting (Flaherty 2004); although manic depression remains the condition most closely associated with creativity (Jamison, op. cit.).

Seizure disorders that lead to tonic-clonic (‘grand mal’) events of the sort that Curtis was known to have suffered in the months before his death are, conversely, equated with lowered levels of creative ability. It is highly probable, incidentally, that Curtis suffered sub-clinical or partial seizures for quite some time before developing tonic-clonic seizures – except in cases where seizures are the after-effect of an accident or substance abuse causing brain damage, this is believed to be the common trajectory of the condition. Early film of Curtis on and off stage reveals episodes whose outward appearance at least mimics that of simple partial seizures, for example, prolonged eye flutters (Waltz 2001). There are also numerous reports (for example, accounts given in Curtis 1995) of sudden and uncharacteristic emotional outbursts, which are also characteristic of partial seizures (Waltz, op. cit.).

There is, of course, considerable danger in the practice of posthumous diagnosis, not least when it comes to discussing creativity. Some neuroscience literature insists on pathologising the musicality of individuals with neurological impairments as a form of ‘savant syndrome’ rather than an authentic talent that happens to occur in a person with a disability. In addition, binding disability and creativity tightly together permits the ‘triumph over adversity’ narrative to again take centre stage, which may sell tickets but calls the authenticity of the art and the artist into question. In this case, a particular experience is sold to an audience keen to appreciate and feel part of an uplifting tale of perseverance.

As noted, neither Joy Division nor Factory Records ever discussed Curtis’s seizure disorder and depression in public. Even after his death, disability was not remarked on at all in interviews by his former band members, later performing under the name New Order, until around the release of their album Power, Corruption and Lies (1983). The first discussion of epilepsy in a related marketing campaign came in the PR materials for Deborah Curtis’s book Touching From a Distance (1995). This book formed the partial basis of Anton Corbijn’s 2007 film, Control. Along with the Joy Division documentary (Gee 2007) and the reissues mentioned earlier, these were marketed with materials that made explicit reference to Curtis’s health status.

It makes sense that in writing a personal memoir, Deborah Curtis would discuss the impact of her husband’s illness and subsequent suicide. It seems as though the publication of these details gave permission to those marketing other Joy Division products to broach the subject in their own marketing materials, and certainly it emboldened journalists to start including questions about it in almost every subsequent interview. It is interesting, however, to note how this information is employed. To use a quotation from the press packet for the Gee documentary’s premiere at the Toronto Film Festival:

As Curtis’s late developing epilepsy emerges through the retelling, it becomes irresistible not to see it as some kind of external manifestation of his inner turmoil, especially when tied to footage of his increasingly frenzied dancing. It is shocking, but entirely believable, to hear that no one in his inner circle tried to communicate with Curtis about his illness or make any concessions on his behalf (on one occasion, in fact, picking him up from hospital so as to not cancel a show). But then, as drummer Stephen Morris notes, where he came from they rode pigs for entertainment and therefore, presumably, didn’t have such complicated things as feelings. (emfoundation 2007)

In this excerpt, epilepsy becomes part of an ideological construct completely enmeshed within the discourse of Romanticism, external difference as a marker for internal sensitivity. To some extent this can be observed in the work of Paul Morley, the journalist most closely associated with Joy Division. In his book, Joy Division Piece By Piece: Writing About Joy Division 1977–2007 (2008), it’s as though a dividing line is inserted at approximately page 115 – the moment when he stops writing mostly about music and the Manchester scene, and starts writing about illness, death, suicide and emotion alongside some music. As his writing travels past 1978, when he describes Ian Curtis as purely a musician – ‘flat and intent, a fourth instrument’ – and through the fateful events of 1980, Curtis becomes ever a symbol or dramatic character in a larger narrative. In his sleeve notes for the CD reissue of Closer (2008), for example, he is ‘singer Ian Curtis, who had less than two months to live, and sort of knew it’ (p. 126). In each of the later interviews, essays and reviews Morley includes, discussions of the music are necessarily bracketed by at least some discussion of Curtis’s health.

The press kit for Anton Corbijn’s film Control continues the trend. The first paragraph of the short synopsis ends:

The strain manifests itself in his health. With epilepsy adding to his guilt and depression, desperation takes hold. Surrendering to the weight on his shoulders, Ian’s tortured soul consumes him. (Northsee Films Ltd. 2007)

Again, we see illness explained as an inner expression of outer turmoil. The press kit repeats the ‘tortured soul’ phrase twice, adding a ‘tragic’ here and there for good measure. Press coverage, of course, followed the lead of the material provided to journalists: most articles included the adjectives ‘tragic’ or ‘troubled’, often in the headlines.

One must ask – why the change? What has made publicists and journalists see disability not as an issue to be covered up or avoided, as it was during Joy Division’s existence and shortly thereafter, but as something to be highlighted? One answer is that it has been adopted as a mark of authenticity in an industry that finds such evidence in increasingly thin supply.

In his proposal of three processes of authentication, Alan Moore’s first- and second-person authenticity provide a useful model through which to discuss the case of Ian Curtis and Joy Division. Moore states that first-person authenticity, or ‘authenticity of expression’, ‘arises when an originator succeeds in conveying the impression that his/her utterance is one of integrity, that it represents an attempt to communicate in an unmediated form with an audience’ (Moore 2002, p. 210). These can be viewed through ‘extramusical’ actions, which directly convey a sense of emotion. In Curtis’s case, his lyrical content is unavoidable, especially in the period immediately after his suicide. Such lines as:

The strain’s too much, can’t take much more

Oh I’ve walked on water, run through fire

Can’t seem to feel it anymore

It was me, waiting for me

Hoping for something more

(‘New Dawn Fades’, from Joy Division, 1979)

suggest deeply felt emotion, subsequently authenticated by Curtis’s actions, which in the dialectic of Romanticism can be interpreted as part of an authenticating performance. Furthermore, Curtis’s intense on-stage performances inspire a communal first-person response to the growing but hidden presence of epilepsy.

Moore’s concept of second-person authenticity, or the ‘authenticity of experience’, ‘occurs when a performance succeeds in conveying the impression to a listener that that listener’s experience of life is being validated, that the music is “telling it like it is” for them’ (ibid., p. 219). In this instance we can see the authenticating actions of the post-punk scene, which sought to move beyond punk rock’s failed break with tradition by embracing a definition of punk as ‘an imperative to constant change’ (Reynolds 2005, p. xvii). Joy Division’s image spoke directly to the band’s followers who were attempting to outwardly represent political dislocations of the era. As Reynolds points out:

The post-punk era overlaps two distinct phases in British and American politics: the centreleft governments of Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan and Democratic president Jimmy Carter, who were then near simultaneously displaced by the ascent of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, respectively – a swing to the right that ushered in twelve years of Conservative politics in America, and a full eighteen in Britain. (ibid., p. xxv)

The post-punk scene emerged into this confusion and attempted to grapple with the contradictions. Among the conceptual concerns that quickly entered into the post-punk discourse was the sense of Armageddon proposed by the very real threat of nuclear war. So, where punk had responded to mass unemployment with naïve calls for anarchy or, in The Clash’s case, ‘Complete Control’, post-punk artists wrapped the anger up in a more Romanticised, literary, existentialist vision that illustrated just what ‘no future’ meant. Joy Division’s bleak soundscapes, mournful vocals and emotionally raw lyrics combined with their dour (but no less political than punk’s shock style) brown shirt and trenchcoat image created a visual representation of industrial Britain in a state of colourless decay. Thus Joy Division were key to the aestheticism of this era. They were ‘telling it like it is’ for the youth of the time (some of whom were listening), and their telling employed a range of devices through the multifarious meanings of music, lyric, image and marketing.

Outsider art / outsider music

An analogy can be drawn to the role of ‘outsider art’ in the fine art world, art created by an untrained folk artist, often with mental or physical disability, which came to the attention of major collectors in the 1970s. What collectors are buying is not validation of the talent of artists who happen to be disabled, but an ‘ideology of authenticity’ in art: these artists are ‘close to the unconscious’, a gallery owner tells researcher Gary Allen Fine (quoted in Fine 2003, p. 160). Fine notes that when an artist is placed in the ‘outsider’ role by gallery owners and reps, it becomes a powerful and carefully guarded sales tool. ‘In their outsider role, separate from images of a corrupt elite, they are ostensibly ennobled in a form of identity politics . . . Life stories infuse the meaning of the work. It is the purity or unmediated quality of the production of the work, in the view of its audience, that provides the work with significance, and, not incidentally, with value as a commodity’ (ibid., pp. 155–6). He continues to delineate the criteria by which an artist can be ‘included’ in the label of ‘outsider’: uneducated, uninfluenced, poor, Black, disabled, or better yet, some combination of these. Fine links this discourse of ‘authenticity’ (often manufactured) directly to music marketing, particularly in the country genre – though obviously it is now key to rock and roll as well. John Windsor has written in the outsider art journal Raw Vision that holding on to outsider status can take hard work – unless you have an innate attribute such as race or disability that acts as a permanent marker for authenticity:

It isn’t easy being an outsider. Once elected, there are appearances to be kept up: the solitary lifestyle, the nutty habits, the freedom from artistic influences . . . In the end, the outsider’s surest way of proving his integrity is to be dead. (Windsor 1997, p. 50)

These traits, unlike poverty or lack of training, cannot change and are therefore more powerful when deployed in marketing discourse. After all, even as slick a pop artist as Jennifer Lopez can, by virtue of race, readopt a ‘street’ persona and make a claim to still be ‘Jenny from the block’ within this discourse.

Disability provides an even more powerful permanent marker of outsider status. Already there is a small but growing genre called, in homage to outsider art, ‘outsider music’. Its stock in trade is the work of disabled musicians such as the late Wesley Willis, Black and diagnosed with schizophrenia, and Daniel Johnston, who has bipolar disorder. As in fine art, this form of marketing is echoed in how more mainstream artists are now retailed. Musicians working in edgy alternative genres like ‘lo-fi’ and ‘anti-folk’, for example, tend to tie themselves particularly closely to outsider music (as in the example of alternative musician Jad Fair collaborating with Daniel Johnston) as a way of establishing authenticity by association.

And should a musician in an even more mainstream genre, such as straightahead guitar rock, happen to have a diagnosis, it is now immediately seized upon as a potential marketing device. Curtis, at least, was spared this potentially dangerous form of commercial exploitation. The story of Australian band The Vines provides a cautionary tale as to the potential effects on musicians with disabilities themselves. Lead singer Craig Nicholls’ wild on- and off-stage behaviour was the stuff of legend from 2002 to 2004 – a legend carefully played up by his record company’s publicists. Nicholls, they noted in press releases, lived on a diet of hamburgers and cola only, ignored or insulted journalists, and occasionally attacked band members on stage, where he seemed to be in a world of his own.

In 2004, despite warnings from the band that Nicholls was not in good shape mentally, his record company sent the group on another world tour. The singer ended up being arrested for assault, alienated TV chat-show hosts and fans alike, and came close to a complete nervous breakdown. ‘He really was in pain, and it was awful to watch’, the band’s current manager told a journalist in 2006. ‘I used to sometimes think, on tour, “Are we gonna be the end of Craig? We love him and yet . . . Why are we making him go on tour when it clearly makes him so unhappy?”’ (McLean 2006). The reason, of course, is that it was precisely Nicholls’s outrageous, over-the-top behaviour that was making money. It gave The Vines something that made them stand out from the raft of Strokes-style guitar bands on the circuit, a quality of ‘authentic’ unpredictability and potential menace that sold tickets and records. One could compare the punter-attracting excitement with the ‘will he show up or won’t he?’ factor of any appearance by Pete Doherty.

In the end, a roadie’s intuition led Nicholls to a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome, a form of autism, a difference that he acknowledges makes live performance a minefield. The band has since largely avoided touring in favour of recording, at the insistence of protective band members, a reasonably sensitive manager, and Nicholls himself, who has gained a greater understanding of his disability and how to manage it (ibid.). This certainly left his management with a marketing problem, which it has apparently solved by using Asperger syndrome as the keystone of its marketing campaign ever since. It is the central feature of the band’s official bio (Mushroom Music Publishing 2006) and the press release for their latest album (Mushroom Music Marketing 2008), for example, both illustrated with a photo that features Nicholls blankly staring from behind a curtain of hair, an image that reflects back typical (mis)understandings of the nature of autism.

Rather than increasing public acceptance of disability as a natural human phenomenon, this marketing trend risks playing into narratives of enfreakment that objectify people with disabilities and diminish the innate qualities of their creative work. As profoundly shown across multiple musical disciplines in Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music (Lerner and Straus 2006), music practices, their presentation, and even their appreciation in social settings have historically served to buttress popular notions of normalcy. When deployed, the figure of the disabled musician can be used as a humorous device, an example that confirms prevailing stereotypes, or a vehicle for catching up audiences in the ‘overcoming adversity’ narrative. Like race and gender, disability is most typically used in marketing discourses to delineate the boundaries of normalcy rather than to expand them.

This process both conflicts and coincides with other discourses that operate within popular music. As Simon Frith writes, ‘for the last thirty years . . . pop has been a form in which everyday accounts of race and sex have been confirmed and confused’ (Frith 2004, p. 46), a process that now extends to disability. At the same time:

The rock aesthetic depends, crucially, on an argument about authenticity. Good music is the authentic expression of something – a person, an idea, a feeling, a shared experience, a Zeitgeist . . . ‘Authenticity’ is, then, what guarantees that rock performances resist or subvert commercial logic. (ibid., p. 35)

Of course, if one takes the marketing narrative too far, or makes its congruity with commercial logic too obvious, the target group will rebel. Already some observers have flagged up what they see as Joy Division re-marketing overkill. Fan reactions to an announcement that Microsoft will be releasing a ‘branded’ Joy Division version of its Zune MP3 player in 2008 included comments like: ‘Could this marketing plan be any more lame?’ and ‘If we get depressed will we be able to hang ourselves with the included zune sync cable?’ (anonymous responses to Van Buskirk 2008).

According to Frith, ‘the experience of pop music is an experience of placing: in responding to a song, we are drawn, haphazardly, into affective and emotional alliances with the performers and with the performers’ other fans’ (Frith 2004, p. 37). For some fans, the exposure of an artist’s disability may somehow validate their own personal experience of disability, or the experience of being an ‘outsider’ that the code of disability may be used to signify. Accordingly, the (re)marketing of Joy Division exists within this tension between triangulated points. There is the music marketing industry’s need to establish ‘authenticity’ and its willingness to do so through promotion of indelibly marked bodies. There is the actual emotion and originality of sound reproduced in the group’s music. Finally, there is the fan’s desire to incorporate these into individual and collective experience.

© Mitzi Waltz † Martin James‡ & Cambridge University