New Order’s Blue Monday was released on 7 March 1983, and its cutting-edge electronic groove changed pop music forever. But what would it have sounded like if it had been made 50 years earlier? In a special film, using only instruments available in the 1930s – from the theremin and musical saw to the harmonium and prepared piano – the mysterious Orkestra Obsolete present this classic track as you’ve never heard it before.

Singularity

Footage taken from ‘B-Movie: Lust & Sound In West-Berlin 1979-1989’.

Inside New Order’s Triumphant Return to Dance-Rock

It took a crisis to reunite New Order. The pioneering dance-rock group had ostensibly called it quits in the latter half of the Aughts, but in 2011, they learned that their friend, “Blue Monday” and “True Faith” video director Michael H. Shamberg, had taken seriously ill. So the band regrouped and booked some gigs to raise money for his medical bills.

Originally, the band — which consists these days of frontman Bernard Sumner, drummer Stephen Morris and returning keyboardist Gillian Gilbert (who had left in 2001), along with guitarist Phil Cunningham and bassist Tom Chapman — was set to play only three gigs. But Sumner, who is age 59 and typically soft-spoken, says the reunion snowballed. “We’ve been on tour for three-and-a-half years off and on,” he says from his home near Macclesfield, England. “It seemed like the opportunity to write an album.”

New Order’s first record of new music in 10 years — and first without founding bassist Peter Hook, who acrimoniously departed the group in 2007 — sounds like a triumphant rebirth, their best record since 1989’s Technique. After two LPs of largely guitar-oriented alt-rock in the 2000s, the new album, the 11-track Music Complete, signals a return to kaleidoscopic synthesizer-driven dance-rock. From its wistfully melancholic opener, “Restless,” to its uplifting, poppy closer “Superheated,” and its diversions into bouncy house piano (“People on the High Line”), dusky, poetic tableaux (“Stray Dog”) and ebullient alt-pop odysseys (“Nothing but a Fool”), it shows everything the band — now in its 35th year — is capable of, without ever lagging. Moreover, guest appearances by Iggy Pop, the Killers’ Brandon Flowers, La Roux singer Elly Jackson and former Primal Scream singer Denise Johnson blend in and add to tracks rather than serving as distractions. Like its title, the album is indeed music complete, well thought-out and executed.

“It still sounds like New Order,” says Morris — who is age 57, quick to make jokes and lives in the same area as Sumner — with a laugh. “We’re not trying to be New Order on this record, because why the hell should we? It all jells really, really well.”

Before the group could really get back to business, though, they had to deal with some unpleasantness. Months after what became their last gig with Peter Hook, who had co-founded both New Order and Joy Division with Sumner and Morris, the band had to rebuke the bassist’s claims in mid-2007 that they had broken up. “New Order have not split up,” Sumner and Morris said in a joint statement that summer. Hook retaliated by threatening to sue them.

“What actually happened was we wanted to take a few steps back from New Order, just to get away from it for a little bit,” Sumner says. “So I made a Bad Lieutenant album. Gillian got ill; she had breast cancer. So Steve [who married Gilbert in 1994] had to make sure she was OK. So he looked after her, spent time with her and their kids. She got through it all and made a full recovery, which I’m glad to say. So when Bad Lieutenant reached its conclusion, we were like, ‘What are we going to do next? ‘Cause I could make a Bad Lieutenant album or we could do New Order again.’ And then we got the request to play the charity gigs for Michael.”

“That was when we asked Gillian if she would be open to doing it, and she said, ‘Yeah,'” Morris says. “He was a great friend of ours; he sadly died last year. But it was, you know, the idea of doing something for Michael, for a friend, that got us together.”

Meanwhile, Sumner consulted with his lawyers, who assured him that New Order could carry on without Hook, who subsequently formed his own band, Peter Hook and the Light, which plays Joy Division and New Order material, and authored books about his time in Joy Division and the Haçienda nightclub that New Order co-owned. As of this past April, the bassist reported that he had ongoing legal action with his former bandmates, suing them over the use of the New Order name and trademark. A rep for Hook did not return a request for comment in time for the publication of this article.

What happened since the split, though, has amounted to a nasty, public back-and-forth between the two parties. Last October, Hook penned a negative review of Sumner’s memoir, Chapter and Verse: New Order, Joy Division and Me — which is getting a U.S. release on November 3rd — taking issue with accounts in the book where Sumner said Hook started arguments with him.

“It’s a real shame,” Sumner says. “My heart bleeds for him. He left the band, and then he complained about leaving the band. But I wish him good luck and that he gets on with what he’s chosen to do instead of calling me all sorts of names. He’s so angry. If you choose to take a path in life, don’t blame other people for the path you’ve chosen to take.”

“I really don’t like it when members of bands slag each other off in the press,” Morris says. “If you’ve got a problem, you should sort it out without going public. It’s not very pretty, is it?”

“It must be getting a bit boring for people,” Sumner says. “He did leave a bad taste in my mouth. … I think we made some great records with Peter. I would never diss what he’s done as a musician. But we couldn’t get on together, so he’s gone off to do his thing and it’s his choice.”

Once New Order decided to carry on with their own thing and make what would become Music Complete, they had to decide what direction they would take. Feeling burnt out on making guitar records — as both 2001’s Get Ready and 2005’s Waiting for the Siren’s Call had leaned heavily on the instrument — Sumner decided he wanted to make a dance record. As it happened, Morris had also been getting back into dance music after remixing a track by the electronic group Factory Floor. And when Rolling Stone polled the pair independently of one another about their music tastes, both Sumner and Morris declared themselves fans of Hot Chip. So a dance record seemed to be what the universe was telling them to make.

“It just seemed like the time is right now to return to synthesizers and electronics, and it was interesting to see the way that technology has advanced,” Sumner says. “We can now do what we’ve always wanted to do.”

Morris and Gilbert began working on song ideas, which they filtered through Sumner. They revisited their love of Italo-disco for what would become Music Complete‘s “Tutti Frutti” “When we started up, we used to listen to a lot of Italian electro records,” Morris says. “I really have no idea who they were even by. This guy just used to send us mixtapes, and you’d just play them in the car. That’s all we had in the car, this tape of Italian electro. So since it was an early influence, we decided to get a bit of Italian playfulness in it.”

Things really got started, though, when they brought in a co-producer with a notable dance background: Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowland. “We thought we might as well get a bloke who’s got more synthesizers than us, and he was the only one we could find,” Morris says with a laugh. “We worked on ‘Singularity,’ which was an idea of Tom’s, and we did ‘Unlearn This Hatred,’ which we started with just lyrics and no music.”

The first song they felt comfortable playing live, though, was “Singularity.” The group debuted it in South America during the spring of 2014, but the band wasn’t ready for it to take off — at least in the way it took off. “We didn’t have a title for it, just a working title, ‘Drop the Guitar,’ because it was written with a guitar in drop-D tuning,” Sumner recalls. “I told Steve at the first gig, ‘We’ve got to get a bloody title. Why don’t we all just sit down and think of a title of the song?’ But it never happened. So the first time we played it, somebody must’ve picked up the set list. The next fucking day it was all over the Internet. ‘New Order played a great new song. It’s called “Drop the Guitar.”‘ Fucking hell. That night we thought of the title ‘Singularity,’ which, as I understand it, is the point at which artificial intelligence overtakes human intelligence. And then there’s ‘singularity,’ which refers to the beginning of the universe.” From there, it was on.

One of Music Complete’s most fascinating aspects is the guests who make appearances on the record. All of them came about organically, and in the case of Iggy Pop — who provides the deep poetry recitation on “Stray Dog” — it was a full-circle moment for the band. As it turns out, Iggy was a uniting force for Joy Division early on, especially between Sumner and the group’s now-deceased singer Ian Curtis.

“We’d put an advertisement up in Virgin Records in Manchester for a singer for a punk group,” Sumner recalls. “We didn’t have a name for it yet, but we were a punk group. We weren’t a punk group really, but anyway. And I get all these nobs calling my mother’s house, ‘cause she had a phone, and I still lived with her then. I got all these lunatics calling and we’d audition them and they would be a disaster. This went on for three weeks and it was driving us crazy. Then Ian called, and I recognized his voice, just seeing him at concerts, at punk gigs. And I said, ‘Are you Ian, that Ian Curtis guy?’ He said ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ And I said, ‘You can have the job.’ I didn’t audition him. I didn’t tell him what we’d just been through; I just gave him the job. I just thought it was all right. I knew him from the gigs, and I knew he liked good music, similar to us.

“I went round to meet him at his house, just to talk about rehearsals,” he continues. “It was the week that the Idiot album had come out by Iggy, produced by David Bowie, and Ian said, ‘Listen to this, listen to this, it’s just come out.’ And he played me The Idiot and it was fucking great, in’nit. And I was blown away by it. So Ian kind of introduced me to Iggy.”

“We went to see Iggy right after The Idiot came out,” Morris says. “It was in Manchester, and it was quite strange because I was at that gig, and Bernard was at that gig, and Hooky was at that gig, and Ian was at that gig, and basically everybody we know now was at that gig, but we never knew each other. It was really strange. It’s one of those things, ‘Do you remember Iggy at the Apollo?’ ‘Oh, I was there.’ It’s like the Sex Pistols all over again.” (Sumner and Hook formed Joy Division after attending a Sex Pistols concert.)

In 2014, the organizers of the Tibet House benefit at New York’s Carnegie Hall invited Sumner to perform alongside Iggy Pop. The pair ended up singing Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” at the event. “It was amazing,” Sumner says. “I can imagine Ian smiling when we did it. It would have meant a lot to him.”

Later, Sumner found himself writing stanzas to a poem while watching TV on a night off. Whenever he’d get bored, he’d jot down a line. When he was done, he figured it would sit well over some music Morris and Gilbert had written, the track that would become “Stray Dog.” On a whim, he emailed his new acquaintance to see if he’d sing on it. He got a reply: “Hi Bernard, it’s Iggy. Yes, I can do this.”

“The only time that I’d met Iggy was a result of this,” Morris says. “It was really embarrassing because I had the first Stooges album and it was amazing, but it was on really, really think vinyl. It was a really heavy record. Physically, it was like the thickest record that I had. So the only time I met him, I said, ‘That first Stooges record, man. That was a really heavy record. Oh, God. I meant it weighed a lot. Not that it was …. Oh, fuck. I’ve really made a mess of this, haven’t I?’ He thinks I’m a right idiot.” He laughs.

“When I heard what Iggy did with [‘Stray Dog’], I was amazed,” Morris continues. “It’s like a little film.”

A few months after Sumner sang with Iggy, New Order met another one of their Music Complete guests — La Roux’s Elly Jackson, who provides backup vocals on “Plastic,” “People on the High Line” and “Tutti Frutti” — after watching her open up for them. But in this instance, she felt nervous meeting about meeting the group that had first made her excited about synthesizers.

“You get told things about bands before you meet them that aren’t accurate, especially if they have a reputation, like, ‘Oh, they’ll come say hi, but that will be about it,'” Jackson recalls of the encounter. “Anyway, Bernard came and said hello, and I was chuffed with that, and later on, I went up to their dressing room after the show, and we got to talking about Quando Quango, a band who put out a track called ‘Love Tempo’ on Factory Records.

“I said, ‘You know, it was so weird that [Quando Quango vocalist, DJ] Mike Pickering had produced that,'” she continues. “And he was like, ‘Mike Pickering didn’t fucking produce it; I fucking did.’ And I was like, that’s why I like it so much. It was an amusing moment.”

With the ice broken, Sumner offered her the opportunity to hear some of the tracks that were going on Music Complete, which she said were in a remarkably finished form, and asked if she’d sing on them. “I said, ‘I’ll be your vocal bitch, whatever you want me to do,'” Jackson recalls.

“We watched her onstage, and we were all very impressed with her voice,” Sumner says. “She was great to work with. She is very sweet, and she worked really quick. I think her voice, you know, is a nice counterbalance to mine.”

“Singing with New Order is something I would have wished for when I was 18, and now I know what it feels like,” Jackson says. “It’s lovely.”

The other massive New Order fan to make an appearance on Music Complete is Brandon Flowers, who owes a unique debt to the band. When the group made a video for “Crystal,” the first single off their 2001 album Get Ready, the clip featured a video that followed around a fictional band called the Killers. Flowers and Co. took their name from the video.

New Order and the singer have been friendly with each other over the years. This past May, Sumner even joined Flowers at a solo gig where they sang New Order’s “Bizarre Love Triangle” together. So it was hardly surprising when it was revealed that Flowers sings on the cheerful Music Complete closing track “Superheated.”

“He still owes us money for using the name,” Morris says, joking. “He’s paying us off by singing on our record.”

The whole experience of working with so many guest artists has been inspiring to Sumner. “It’s just interesting, like discovering a new color and putting it on this palette,” he says.

When Sumner and Morris speak to Rolling Stone, they’re both in the midst of reworking the songs on Music Complete into extended versions. Each of elongated versions will appear on a deluxe vinyl edition of the record.

“I’m trying to figure out what ‘Singularity’ is going to turn out like, so I don’t know about that one,” says Morris, who prefers extended versions of songs over the edits and remembers arguing with New Order’s label over keeping “Blue Monday” at seven-and-a-half minutes. “But ‘The Game,’ which seems quite short on the album, goes into a big long guitar solo at the end. It’s kind of turned into some kind of electro-epic and it sounds really completely different.”

By their own accounts, New Order still feel fresh in the journey they started out on, despite a few speed bumps here and there. After the record comes out, they’ll be hitting the road in the U.K. and Europe beginning in November and into December.

Although they’re showing no signs of stopping, the album title — a pun on the electroacoustic music genre musique concrète — begs the question, does “music complete” mean an end? “We weren’t thinking people would think, ‘It’s your last record, isn’t it?'” Morris says. “We didn’t think it meant that. It also doesn’t mean, ‘Oh, bloody New Order has got a new compilation. We just thought it fits, because it’s like a few different styles of music.”

“I think the title was the last thing we did,” Sumner says. “We were completing the album, music complete. It just felt right.”

© Rolling Stone

Peter Hook: “Avec Joy Division, on se marrait beaucoup”

L’ancien bassiste du groupe sort Unknown Pleasures, Joy Division vu de l’intérieur, un ouvrage où il prend le pouls d’une époque et raconte son Joy Division.

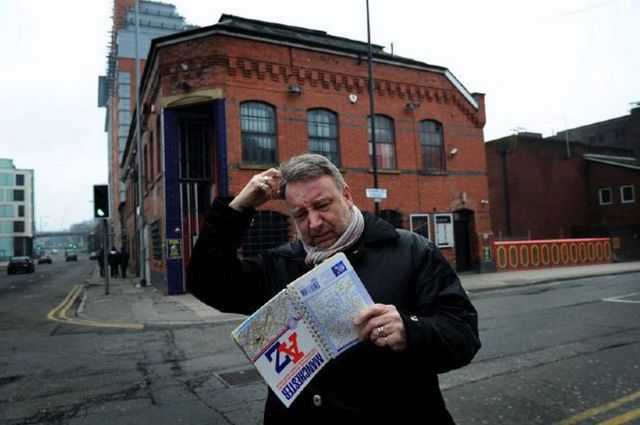

Mardi 22 janvier. Dans un hôtel près de la gare du nord, l’ancien bassiste de Joy Division et de New Order affiche une mine ravie. La veille, il a présenté son dernier livre Unknown Pleasures, Joy Division vu de l’intérieur (ed. Le mot et le reste), devant un parterre de vingtenaires admiratifs. Façon de constater que l’aura de Joy Division, groupe cultissime de la New Wave, n’a pas faibli. En effet, de Lescop à Aline, le nombre de formations qui se revendiquent de la formation mancunienne ne se cesse de croître. Aujourd’hui, Peter Hook ne joue plus avec New Order mais il parle de sa musique comme une intensité qui ne laisse aucunement présager son âge, 56 ans. Avec son accent à couper au couteau et sa gouaille inimitable, il revient pour nous sur la brève carrière de son ancien groupe, l’un des meilleurs groupes du monde, Joy Division.

Pourquoi avez-vous eu envie d’écrire ce livre sur Joy Division maintenant?

Le livre que j’ai écrit sur l’Hacienda (L’Hacienda, la meilleure façon de couler un club ed. Le mot et le reste) m’a vraiment mis en confiance. Ca, c’est pour l’aspect technique, pour l’écriture. Mais sur le fond, je crois que c’est parce que j’ai lu trop de livres sur Joy Division. Toutes ces fautes, toutes ces approximations… Et ça m’a agacé. J’ai du lire le livre de trop, voilà. Mais Unknown Pleasures était compliqué à écrire. En me souvenant de Joy Division, du groupe, de Ian, j’avais systématiquement l’impression que tout était absolument génial. Je faisais des listes et je notais les concerts: 10/10, 10/ 10, 10/10… Il a fallu trouver des nuances et mettre en marche mon sens critique. Ce qui n’était pas évident.

Pourquoi l’avez-vous appelé Unknown Pleasures, d’après le nom du premier album de Joy Division. Quel sens donnez-vous à ce titre aujourd’hui?

Ce disque est la chose la plus déterminante de ma vie. J’ai mis un certain temps à m’en rendre compte. Quand l’album est sorti, je ne l’aimais pas. La production me déplaisait. Je trouvais l’ensemble trop sombre, trop épuré, trop clinique. L’atmosphère punk de nos répétitions et de nos concerts n’y était pas. J’ai mis des années avant de pouvoir le réécouter. Quand Ian est mort, nous nous sommes jetés à corps perdu dans New Order parce que nous n’avions pas le choix. Il fallait refouler. Ca n’était pas très sain, mais ça a marché. Je crois que la puissance de New Order provient précisément de ce refoulement. En 2006, quand j’ai quitté le groupe, tout m’est revenu en pleine figure.

En vous lisant, on a l’impression que vous cherchez à donner une autre image de Joy Division, à banaliser la vie du groupe, à humaniser Ian, en racontant des blagues débiles par exemple. Ca vous agace cette image de groupe culte et mortuaire qui colle aux baskets de cette formation?

Nous venions d’un univers prolétaire, nous étions des ados et franchement, on se marrait beaucoup. La musique était une question de vie ou de mort, certes, mais tout ce qui se passait autour était vraiment super. Ian adorait rire, il avait un sens de l’humour décapant. Il se déguisait souvent par exemple! Comme le bon anglais qu’il était. Bref, oui, l’enjeu était de le démystifier tout en montrer l’admiration profonde que j’ai pour lui. C’était quelqu’un qui avait beaucoup lu, sa culture musicale était considérable. Le bonhomme est devenu tellement culte maintenant que c’est difficile de parler de lui. Dans un magazine anglais, quelqu’un a écrit que je “profanais sa mémoire” par exemple. Ca n’a aucun sens, c’était l’un de mes meilleurs amis.

Comment expliquez-vous qu’il se soit intéressé à l’avant-garde musicale et à la littérature si tôt?

C’était un grand autodidacte. Un type super curieux. Il y a des gens comme ça…

Le public vous renvoyait quelle image à l’époque, pendant les concerts?

Des punks austères et plutôt frimeurs. Mais les gens ne savaient rien de nous. Il faut remettre les choses dans leur contexte, nous sommes devenus connus bien plus tard. A l’époque nous ne mettions pas nos visages sur nos albums par exemple. C’était perçu comme un truc bizarre. Notre nom n’était même pas inscrit sur notre premier disque d’ailleurs…

Pourquoi cet effacement volontaire?

C’était l’éthique du Punk. L’esthétique DIY, contre l’exaltation de l’ego. Et puis on a toujours trouvé que les groupes qui se montraient sur les couvertures de leurs disques avaient l’air de gros cons.

Vous décrivez Ian comme quelqu’un à la personnalité éclatée: un père de famille fauché, un leader de groupe de punk, un grand malade, un amant romantique et impuissant. Réconcilier toutes ses facettes de sa vie était au dessus de ses forces?

Ian est mort à 23 ans… C’est l’âge de mon fils aujourd’hui. 23 ans, c’est le début de la vie. Ca me brise le coeur. On a tellement profité avec New Order, on a connu la gloire et tout ce qui va avec. Lui n’est jamais sorti des clubs miteux, il n’a connu que les vans pourris. S’il était resté en vie, il aurait chanté sur Blue Monday, j’en suis convaincu. On aurait tout fait, ensemble. Power Corruption and Lies aurait était écrit sous le nom de Joy Division. Il aurait fait Glastonbury. Il aurait tourné aux Etats-Unis. Il aurait vu sa fille grandir. Il aurait connu le succès. C’est une injustice absolue et je ne peux rien y faire.

Au début du livre, vous écrivez: “Si on faisait de la musique on héritait automatiquement du statut de lépreux social”. Aujourd’hui, le rock s’apprend à l’école. Pensez-vous que sa banalisation nuit à sa créativité et sa puissance?

Non, je ne crois pas. Enfin, ce qui compte par-dessus tout, c’est l’écriture. Sur le plan formel, le curseur s’est peut être déplacé. Il y a des genres nouveaux, très excitants. Le dubstep par exemple, c’est vraiment super. Mais ça s’est “popifié” très vite hélas. J’adore la House. C’est super drôle, quand je fais des DJ sets, les gens s’attendent à ce que je joue de l’indie, des trucs super dark. Et je ne joue que de la House en fait. Aujourd’hui, le problème c’est peut-être que les groupes deviennent connus vite hyper vite. Le fait de tourner longtemps dans des bars miteux et dans des quartiers pourris, ça rend bon. Mais globalement, je suis moyennement convaincu par cette théorie, très à la mode, du rétro. Quand Oasis est sorti par exemple, je me souviens que tout le monde gueulait: “c’est du réchauffé, c’est pompé des Beatles”. On s’en fout. En vieillissant, on a l’impression que tout ressemble à quelque chose du passé.

Enfin, Joy Division ne ressemblait pas aux Beatles ou autre chose d’ailleurs…

Ca, c’est sûr! Et New Order non plus. (Il explose de rire). Et on est des sacrés connards parce qu’un tas de groupes aujourd’hui nous ressemble!

© L’Express

Que reste-t-il de Joy Division?

Plus de trente ans après sa fin brutale, le groupe new wave de Manchester continue d’influencer la scène rock. Dans un livre, le bassiste Peter Hook entretient le culte.

Agglutinés dans un bar parisien du XIe arrondissement, une bande de gamins écoute religieusement la parole d’un quinquagénaire grisonnant venu de Manchester. Cela fait maintenant une bonne heure qu’il glose sur la dissémination de la classe ouvrière britannique, ravi de capter l’attention d’un parterre juvénile. L’homme qui parle avec un accent à couper au couteau n’est autre que Peter Hook, membre fondateur de Joy Division. Le bassiste est ici pour faire la promotion de son dernier livre : Unknown Pleasures, Joy Division vu de l’intérieur. Le public est venu se confronter à une légende du rock.

L’apparition de Joy Division dans l’histoire de la musique ressemble à celle d’une comète : éphémère et sublime. En 1977, le groupe souffle un vent glacial sur les braises du punk pour inventer la new wave, une musique épurée et droite comme une autoroute. Mais les médias n’ont pas le temps de se retourner. Trois ans plus tard, le chanteur charismatique, Ian Curtis, se suicide (il a 23 ans), mettant fin brutalement à la carrière du quatuor. Joy Division laisse derrière lui deux albums, un titre mythique, Love Will Tear Us Apart. Naissance d’un culte. Pour tourner la page, les musiciens, eux, forment immédiatement New Order, dont le succès international sera durable.

Un gamin débonnaire, fêtard, complexe mais joyeux

De quoi inspirer une génération d’artistes, née pourtant après 1980. “Le groupe est une référence indéboulonnable, constate Jean-Daniel Beauvallet, rédacteur en chef aux Inrockuptibles. Chaque semaine, une nouvelle formation cite Joy Division en interview. Leurs concerts, même vus sur YouTube, restent d’une efficacité redoutable. Adolescent, on ne se remet pas d’un tel choc.”

Le public s’est approprié l’image de Joy Division et il ne veut pas la lui rendre, préférant s’accrocher à des fantasmes. “Je suis très fier que notre musique soit d’actualité, se réjouit Peter Hook, mais je dois aussi assurer le service après-vente et détruire certains clichés.” 600 pages lui ont été nécessaires pour esquisser un autre portrait, “plus juste”, de Ian Curtis. Celui d’un gamin débonnaire, fêtard, fan de foot. “C’était quelqu’un de complexe, certes, mais il était joyeux, poursuit-il. Il nous faisait hurler de rire.” Son propos affectueux est pourtant souvent jugé iconoclaste. “Les médias anglais m’ont accusé de profaner les morts”, regrette-t-il. Pour le rock aussi, la gestion d’héritage est un problème épineux.

© L’Express

How we made: New Order’s Gillian Gilbert and designer Peter Saville on Blue Monday

Gillian Gilbert, synthesiser

In 1983, before computers came along, it wasn’t easy to do electronic basslines and rhythms. So Bernard Sumner started building these gadgets called sequencers. Next, we thought it would be good to create a song that was completely electronic. Blue Monday’s distinctive intro was written on an Oberheim DMX drum machine. We’d been going to clubs in New York and wanted to recreate the fantastic bass-drum sounds we’d heard. We tried to play something like Donna Summer’s Our Love and came up with that instantly recognisable thud.

The synthesiser melody is slightly out of sync with the rhythm. This was an accident. It was my job to programme the entire song from beginning to end, which had to be done manually, by inputting every note. I had the sequence all written down on loads of A4 paper Sellotaped together the length of the recording studio, like a huge knitting pattern. But I accidentally left a note out, which skewed the melody. We’d bought ourselves an Emulator 1, an early sampler, and used it to add snatches of choir-like voices from Kraftwerk’s album Radioactivity,as well as recordings of thunder. Bernard and Stephen had worked out how to use it by spending hours recording farts.

Blue Monday was meant to be robotic, the idea being that we could walk on stage and do it without playing the instruments ourselves. We spent days trying to get a robot voice to sing “How does it feel?”, but somebody wiped the track. Bernard ended up singing it. He says the lyric came about because he was fed up with journalists asking him how he felt. The lines about the beach and the harbour were the start of his many nautical references – he loves sailing. And Peter Hook’s bassline was nicked from an Ennio Morricone film soundtrack.

Blue Monday is a dance track with a hint of melancholy. A seven and a half minute-long single was unheard of, so we put it out on 12-inch. We couldn’t believe it when it became the biggest-selling 12-inch of all time. People have interpreted the title all sorts of ways. It actually came from a book Stephen was reading, Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions. One of its illustrations reads: “Goodbye Blue Monday.” It’s a reference to the invention of the washing machine, which improved housewives’ lives.

Peter Saville, sleeve designer

I met New Order in their Manchester studio to show them a postcard of the Henri Fantin-Latour flower painting I was using for the cover of their forthcoming album Power, Corruption and Lies. While I was there, they played me Blue Monday, and I instinctively understood what they were trying to do. It sounded like something the equipment could play itself.

I picked up an interesting object and asked: “Wow, what is this?” I’d never seen a floppy disk before. I thought it was great. I said: “Can I have it?” And Stephen said: “Not that one!” So I drove back to London listening to a tape of Blue Monday with another floppy disk lying on the passenger seat. By the time I got home, I knew the sleeve would replicate a floppy disk, with three holes cut in it through which you could see the metallic inner sleeve. The only information I had to impart were the words New Order, the song titles (including B-side The Beach) and the Factory Records catalogue number. I decided to do this with a column of coded colours, to provide some mysterious data, so I sat down with some pencils and used a different colour for each letter.

Tony Wilson loved to say the sleeve was so expensive they lost 5p per copy. But it’s unlikely; Factory never talked budgets. Nobody ever said to me: “This is a costly sleeve.” No one sent me a copy, either; I had to go to a record shop. The record sold so quickly that the version I bought had a black sleeve but no holes. The printers hadn’t been able to keep up with demand, so had banged out a cheaper version. I don’t know how many thousands were sold that way, or whether Factory were charged the full price for something they didn’t get, which would be very Factory. But I’m pleased it’s a legendary cover for what turned out to be a classic track: the principal moment of conversion between progressive rock and dance. Similarly, colour codes have become widespread in graphic design.

When Power, Corruption and Lies came out, I put a colour wheel on the back explaining the code. A week later, two letters in NME pointed out a spelling mistake. Four years ago, I was in Switzerland giving a talk and this nice accountant in a suit came up and said: “Do you remember there were letters in NME about Power, Corruption and Lies? I wrote one of those letters.”

© Dave Simpson & The Guardian

Hook si esibirà a Milano, Padova, Roma, Lecce e Giulianova

Ceremony

“Savoir qu’on n’a plus rien à espérer n’empêche pas de continuer à attendre.”

– Marcel Proust, À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs

Je me souviens d’avoir longtemps rangé le premier maxi et le premier album de New Order avec les disques de Joy Division pour former un sorte de triptyque comme en peinture, composé de paires, avec l’album Unknown Pleasures et le 45tours Transmission, puis Closer et le 45tours Love will tear us apart, et, sans la présence de Ian Curtis, Movement et Ceremony, cette dernière étant en quelque sort une suite posthume accouchée dans des conditions plus que particulières, parce qu’il fallait bien continuer.

Je me souviens bien que dans son livre intitulé Joy Division : Piece by Piece, l’écrivain journaliste Paul Morley décrit Love will tear us apart comme la meilleure chanson du monde, puis, une page plus loin, dit de Ceremony qu’il s’agit de la meilleure chanson du monde (comme ça tout le monde est content).

Je me souviens aussi que cette chanson n’a été jouée qu’une fois en live du vivant de Ian Curtis, et qu’après sa disparition, les membres restant du groupe – devenu New Order -, ont du réécouter bon nombre de fois la cassette démo où elle était enregistrée pour pouvoir retranscrite son texte et se le réapproprier correctement, et que dans le cas similaire de la pochette de l’album Closer, très solennelle mais n’ayant aucun rapport direct avec la mort de Ian Curtis, le titreCeremony renvoie bien sûr au chanteur suicidé alors que c’est une chanson qui parle d’amour, avant tout, et écrite de son vivant :

This is why events unnerve me,

They find it all, a different story,

Notice whom for wheels are turning,

Turn again and turn towards this time,

All she ask’s the strength to hold me,

Then again the same old story,

World will travel, oh so quickly,

Travel first and lean towards this time.

Oh, I’ll break them down, no mercy shown,

Heaven knows, it’s got to be this time,

Watching her, these things she said,

The times she cried,

Too frail to wake this time.

Oh I’ll break them down, no mercy shown

Heaven knows, it’s got to be this time,

Avenues all lined with trees,

Picture me and then you start watching,

Watching forever, forever,

Watching love grow, forever,

Letting me know, forever.

Dans ce court roman, qui s’apparente à un monologue intérieur, Bertrand Schefer parle d’enterrement sans jamais prononcer ce mot, auquel il préfère Cérémonie. Dans un style sobre et délicat, il déambule dans Paris et dans Rome, mais aussi dans ses souvenirs, ses années de débauches notamment. C’est aussi une bonne façon de parler du frère, de l’oncle et d’autres personnes encore, d’acheter un beau costume, de parler de l’absente, de comprendre la relation qu’il entretenait avec, d’afficher, à l’extérieur du moins, une peine détachée, jusqu’aux obsèques où il fait ce constat final : il faudra bien continuer. Les éditions POL nous ont habitués à de beaux textes modernes sur la mort –Perfecto de Thierry Fourreau ou, bien sûr, le magnifique Suicide d’Édouard Levé -, et Cérémonie vient s’ajouter à cette liste de publication, pour le plaisir du lecteur pour qui écriture rime avant tout avec littérature, celle-là même qui est l’opposée de l’éphémère et de l’urgence, du temps présent et de l’actualité, celle où l’on peut se perdre, celle de Virginia Woolf (Promenade au phare) ou Julien Gracq (Le Rivage des Syrtes)…

extrait de Cérémonie, de Bertrand Schefer :

“Nous nous sommes vus pendant près de dix ans et pendant deux ou trois ans, je ne saurais dire combien de temps exactement, car tout se déréalisait de mois en mois, nous avons pour ainsi dire cohabité au milieu des disques et de l’alcool, toujours plus bas à chaque visite, mais tenant des discours qui semblaient aussi de plus en plus lucides, des paroles aiguës et acérées sur les productions musicales et littéraires, sur les connaissances, les fausses amitiés, les tentatives amoureuses désespérées, sur ceux qui perçaient et ceux qui s’effondraient, et rien ne semblait à la hauteur de nos exigences car nous raisonnions de plus en plus vite dans les méandres du son qui nous portait, dans le mélange d’alcool et de fumée qui ouvrait de nouvelles perspectives à l’intelligence des choses et nous permettait de déchiffrer l’actualité, les textes et les tendances du moment. Nous avions du mal à interrompre le vertige de cette descente une fois engagée dedans, et c’était toujours la même chose, englués dans la critique de tous les systèmes, des échecs et des réussites, il fallait chaque fois attendre la fin d’un morceau et la dernière goutte d’une bouteille pour réussir à nous arracher au milieu de la nuit à ce monde fait de bribes de phrases lancées dans les vides et conclure par une formule incantatoire, toujours la même : il faut s’y mettre.”

© Yann Courtiau & Manoeuvres de Diversion (Publié le 18 mai 2015)

Joy Division Play Coming in April 2016

A new play which tells the story of one of the world’s most iconic rock bands of the 70s comes to stage in spring 2016. New Dawn Fades – The Story Of Joy Division is a new play by writer/actor Brian Gorman telling the classic tale of four lads who, inspired by the punk revolution, came together to form one of the most influential bands of all time.

The stage version combines the band’s history with the city of Manchester and Salford, taking inspiration from Curtis’ enigmatic lyrics, and involving many real-life characters, such as Johnny Rotten, Tony Wilson and Karl Marx. New Dawn Fades features versions of Joy Division’s most famous tracks, performed live by the actors as part of the performance.

Join ‘Mr Manchester’ Anthony H. Wilson as he takes you on a journey of myth and magic through the history of the world’s first industrial city, meeting the people who emerged from that landscape to form one of Manchester and the world’s most iconic bands – Joy Division.

The late Tony Wilson is played out in all his brilliant pretension, making you laugh at his madness and lovable warmth and misty eyed at his memory.

The band themselves are set in stone in their roles, Hooky is the thug with a heart of gold, Barney the insecure arty one, Steve the shy and quiet one and Ian Curtis the romantic dreamer with a backdrop of domestic drudgery and greyness which is central to this story – Martin Hannett captures the visionary producer and sound sculptor perfectly.Meanwhile, band manager, the loveable Rob Gretton, drives things along in a blunt, forthright and zero showbiz manner.

Wilson mixes Mancunian history into the narrative, interviewing a Roman general on the local news programme, before speaking to John Dee the Mancunian alchemist – the history is important that the radical nature of the city from its history to its music is put into a focus.

Based on fact, this play is funny, serious, sad, enigmatic and not to be missed.

One bleak day gives way to another in Joy Division’s “24 Hours”

Peter Hook plays a six-note bass-guitar riff throughout Joy Division’s “24 Hours,” with slight variations. Sometimes he plays one extra note; sometimes one less. Sometimes the riff walks up; sometimes it starts out in that direction and then suddenly drops off a cliff. It’s almost like Hook’s writing the music in real time, testing out different combinations to see which one sounds best. As the tempo shifts, Hook stays his course. He knows there’s something there: catchy enough to be hummable, yet downbeat enough to make the cheeriest listener feel instantly blue.

It’s tempting to read a lot into the songs on Joy Division’s final studio album,Closer, because it was recorded just over a month before frontman Ian Curtis committed suicide. Anyone looking for clues to Curtis’ mental state could fill an entire notebook with observations on “24 Hours.” Even the first few words—“so this is permanence”—sound like the cry of a man who’s given up. “24 Hours” is a stock-taking song, and what the singer discovers about himself is not encouraging in any way. He seems to think that any window of opportunity he may have had to salvage his relationships or even find any simple happiness has long-since closed. “I watched it slip away,” he moans. Looking beyond today, he’s certain, “There’s nothing there at all.”

So “24 Hours” isn’t exactly upbeat—at least when it comes to what Curtis has to say about his situation. Musically though, this is actually one of the rare uptempo songs on Closer. The rhythms alternate between funereal and almost punky, recalling some of Joy Division’s earliest singles. It bridges every era of the band, in a way that makes it feel all the more final. It’s a last hurrah, encompassing all that Joy Division could be, and distilling the despairing themes of so much of Curtis’ writing.

That’s why the bass line is so vital to “24 Hours”: It propels the song, but also carries the message, sad as it is. After all the different attempts at the central riff, Hook takes one last crack at it, with six more notes. He ends on a down note—inevitably, conclusively, and inescapably.